Table of contents

- The Moment You Hit Enter

- DNS Resolution: Finding the IP Address

- ARP: Locating Your Gateway

- The TCP Three-Way Handshake

- Inside Your Router: Packet Processing

- How Your Router Forwards Data

- Latency vs Bandwidth: The Real Performance Story

- Common Router Bottlenecks

- How to Optimize Your Router Performance

- Conclusion: Your Router Is More Than a Magic Box

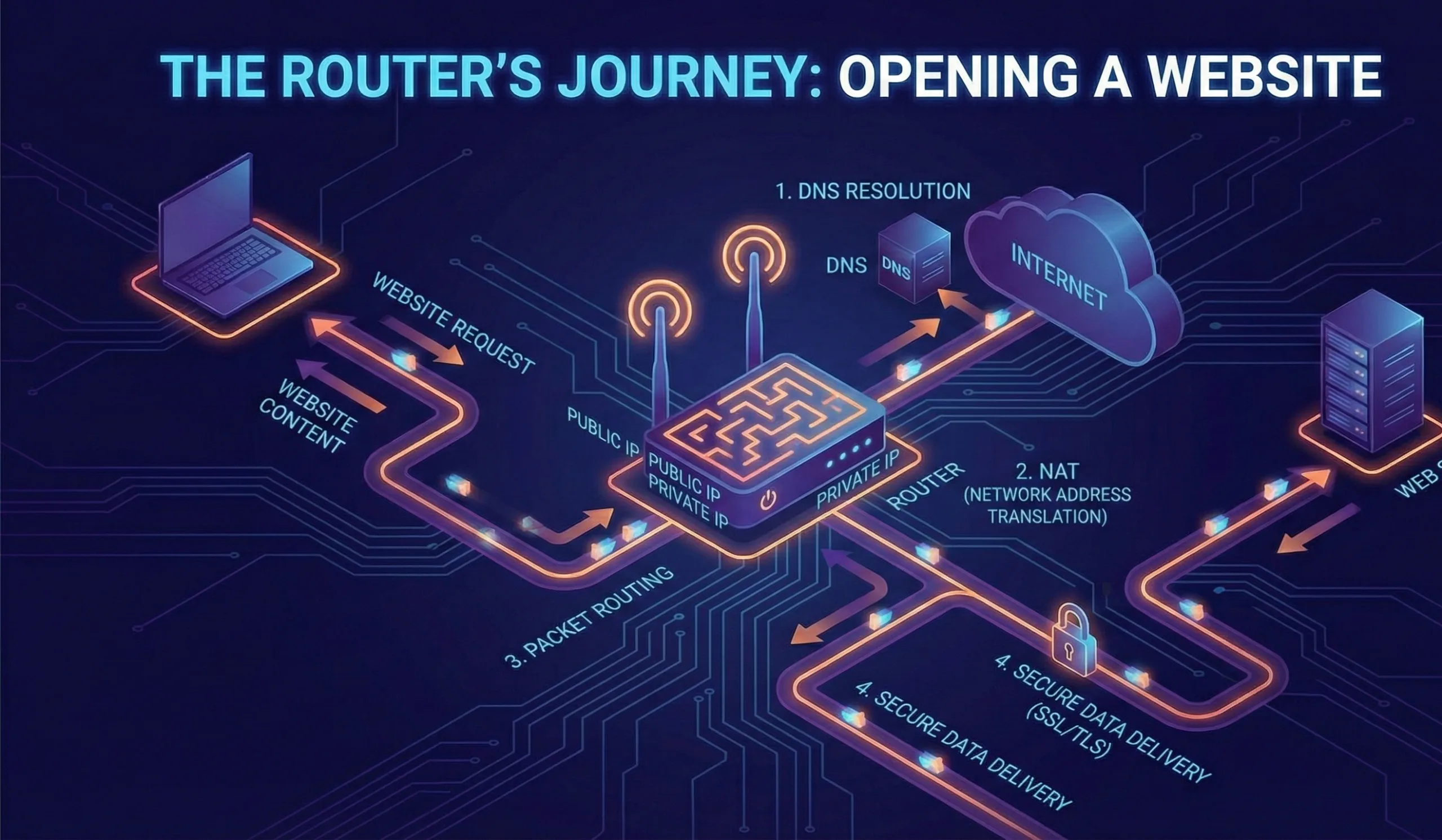

The Moment You Hit Enter

When you type a URL into your browser and press Enter, something remarkable happens behind the scenes—and your router sits right in the middle of the action.

Most people think their browser just magically connects to a website. In reality, a complex series of events involving multiple network protocols, your device’s operating system, your ISP’s infrastructure, and yes, your router, all coordinate to fetch that webpage. Before your router can even forward your request to the internet, several steps must occur.

Your browser doesn’t know how to find websites using their human-readable names. It needs an IP address—a unique numerical identifier—to locate the server. But how does your router factor in? It’s your gateway between your private network and the wider internet, and it plays an active role in translating requests, managing traffic flow, and determining the best path for your data.

Understanding what happens inside your router isn’t just academic. It directly impacts your browsing speed, the reliability of your connection, and your ability to troubleshoot network problems when they arise.

DNS Resolution: Finding the IP Address

Before your router does anything, your browser needs to know where to send the request. This is where DNS (Domain Name System) comes in.

How DNS Works (The Router’s Role)

When you type www.example.com into your browser, here’s what happens:

- Browser Cache Check – Your browser first checks its own DNS cache (you can actually see this in Chrome by visiting

chrome://net-internals/#dns). If it has recently visited this domain, the IP address is already stored locally. - Operating System Cache Check – If the browser doesn’t have the answer, it checks your OS DNS cache. On macOS, you can view this with a simple terminal command; on Windows, the cache is stored similarly.

- Recursive DNS Query – If neither cache has the answer, your browser contacts the DNS resolver configured on your system. This resolver is typically provided by your ISP, though many people configure custom DNS servers like Google’s (8.8.8.8) or Cloudflare’s (1.1.1.1).

The Router’s DNS Forwarding Role

Here’s where your router enters the picture. Your router typically does not perform DNS resolution itself—instead, it forwards your DNS request to the configured DNS server.

When your device sends a DNS query, it reaches your router first. The router examines the packet, sees it’s a DNS request (UDP protocol, port 53), and forwards it to the DNS resolver’s IP address that was configured during your internet setup (usually via DHCP).

The DNS resolver then performs the heavy lifting:

- It checks its own cache

- If not found, it queries root nameservers

- Root nameservers direct it to the appropriate TLD (Top-Level Domain) nameserver for

.com,.org, etc. - The TLD nameserver responds with the authoritative nameserver

- The authoritative nameserver finally returns the actual IP address

- The resolver sends this back through your router to your device

The entire DNS process typically takes 50-300 milliseconds, though cached responses return in under 10ms. This matters because DNS resolution latency is often the first bottleneck users experience when loading a website.

Pro Tip for Router Configuration

If DNS is slow, you can bypass your ISP’s resolver entirely by:

- Setting your router’s DNS settings to use Cloudflare (1.1.1.1) or Google (8.8.8.8)

- Configuring DNS caching on your router if it supports it

- Some advanced routers (like those running OpenWrt) can cache DNS responses locally, reducing redundant queries

For your business infrastructure, this becomes critical. A misconfigured DNS server on your router could mean every user on your network experiences unnecessary latency.

ARP: Locating Your Gateway

Before your device even reaches your router with the DNS request, it needs to know your router’s physical address.

The ARP Protocol

Every device on your local network has two addresses:

- IP Address (logical) – e.g., 192.168.1.100

- MAC Address (physical) – e.g., 00:1A:2B:3C:4D:5E

Your device knows the router’s IP address (it was assigned via DHCP), but it needs to know the router’s MAC address to send frames across the local network. This is where ARP (Address Resolution Protocol) comes in.

When your device needs to communicate with the router, it sends an ARP broadcast asking: “Who has IP address 192.168.1.1?” Your router responds with its MAC address, and your device caches this for future use.

Router ARP Tables

Your router maintains an ARP table of all devices on your local network and their physical addresses. This is why, if you ever had a device that kept losing connectivity, it might have been because the ARP cache got stale or corrupted.

In your router’s admin interface (usually accessible at 192.168.1.1 or 192.168.0.1), you can often view the ARP table to see all connected devices. This is particularly useful for:

- Identifying unknown devices on your network

- Diagnosing why a device isn’t responding

- Managing DHCP reservations for servers or IoT devices

The TCP Three-Way Handshake

Now your device has the website’s IP address. But before any actual webpage data can be transferred, a reliable connection must be established. This happens through TCP’s three-way handshake.

Why TCP Handshakes Matter

TCP (Transmission Control Protocol) is designed to ensure reliable, ordered delivery of data. Before transmitting anything meaningful, TCP establishes a connection through a handshake. Your router witnesses and facilitates all three steps:

Step 1: SYN (Synchronize)

Your device sends a SYN packet to the web server containing:

- Its source IP and port

- The server’s destination IP and port (usually 80 for HTTP, 443 for HTTPS)

- A sequence number (to order future packets)

Your router receives this packet, checks the destination IP, and forwards it toward the internet.

Step 2: SYN-ACK (Synchronize-Acknowledge)

The web server responds with a SYN-ACK packet containing:

- The server’s sequence number

- An acknowledgment of your device’s sequence number

- Its own sequence number for the reverse direction

Your router receives this returning packet and forwards it back to your device.

Step 3: ACK (Acknowledge)

Your device sends an ACK packet acknowledging the server’s sequence number. This confirms the connection is established.

At this point, the connection is open and data transfer can begin. The entire three-way handshake typically takes 50-200 milliseconds depending on distance and network conditions.

Router Connection Tracking

Your router maintains a connection state table (technically called a NAT connection table) that tracks:

- All active TCP connections

- UDP sessions

- Which internal device initiated which external connection

- How long each connection has been active

This is essential because your router performs Network Address Translation (NAT). Your internal device has a private IP address (192.168.x.x), but when it communicates with external servers, the router replaces the source IP with its own public IP address. When responses come back, the router knows which internal device to forward them to based on this connection table.

For busy routers or devices with many connections, this table can become a bottleneck. Some older routers have limited connection tracking capacity, which is why you might experience dropped connections under heavy load.

Inside Your Router: Packet Processing

Once the TCP connection is established, your browser sends HTTP requests for the webpage. Here’s what happens inside your router with each packet.

Layer 3: Network Layer Processing

When a packet arrives at your router’s WAN port, the router’s CPU performs several tasks:

- Packet Header Inspection – The router examines the IP header to determine:

- Source IP address

- Destination IP address

- Protocol type (TCP, UDP, ICMP)

- Packet size and fragmentation status

- TTL (Time To Live) value

- Routing Table Lookup – The router checks its routing table to determine where to forward the packet. For most home routers, this is simple: everything destined for an external IP goes out the WAN port. For more complex networks (like business routers), sophisticated routing decisions are made here.

- NAT Translation – If the packet is outgoing, the router replaces the internal source IP with its public IP. If returning, it performs reverse NAT—converting the destination IP from the router’s public IP back to the internal device’s IP.

- Firewall Rules – The router checks whether the packet should be allowed based on firewall rules. This is where inbound ports are blocked by default, protecting your network.

- Optional Processing – Depending on the router’s configuration, additional processing might occur:

- Deep packet inspection (analyzing packet content)

- QoS (Quality of Service) prioritization

- Traffic shaping or throttling

Layer 2: Data Link Layer Framing

After Layer 3 processing, the packet is encapsulated into a frame with:

- Source MAC address (the router’s interface)

- Destination MAC address (either another router on the path, or the ISP’s modem/gateway)

- CRC (Cyclic Redundancy Check) for error detection

The frame is then physically transmitted via Ethernet, fiber, or wireless depending on the connection type.

Router Processing Delays

All of this happens in microseconds for modern routers, but delays can accumulate:

- Processing delay – Time for the CPU to examine and process the packet

- Queuing delay – Time waiting in a buffer if the router is congested

- Transmission delay – Time to actually transmit the bits onto the wire

- Propagation delay – Time for the signal to physically travel across media

For most home routers, processing delay is measured in microseconds. However, queuing delay can become significant under heavy load. If you’re running a busy torrent client, a security scan, or have many devices streaming video simultaneously, packets will queue up waiting to be processed, adding tens or hundreds of milliseconds of latency.

How Your Router Forwards Data

When your router receives data destined for an external server, it doesn’t just blindly forward it. There’s an entire path-finding process happening.

The Internet Backbone: Hops and Routers

After your packet leaves your router, it travels through many other routers on its way to the destination server. Each intermediate router:

- Receives the packet

- Reads the destination IP address

- Consults its own routing table

- Forwards the packet to the next hop (usually the nearest router in the direction of the destination)

A typical internet request might pass through 10-15 different routers on its journey. You can visualize this path using the traceroute command (or tracert on Windows):

bashtraceroute example.com

This tool shows each hop along the path and how long it takes to reach each router. If a website is slow, traceroute often reveals where the delays are occurring.

BGP: The Internet’s GPS

Behind the scenes, routers use BGP (Border Gateway Protocol) to share information about available routes. Internet routers constantly communicate with each other, advertising which IP address ranges they can reach and how many hops it takes. This allows the internet to dynamically reroute traffic if a link goes down.

Your ISP’s routers participate in BGP, which is why your home router’s packets find their way to websites across the world.

The Return Path: Asymmetry

Interestingly, the path data takes to a server doesn’t necessarily match the path responses take back to you. The internet’s routing is dynamic and can change minute-by-minute. This is why latency is measured as round-trip time (RTT)—the time for data to reach a server and return.

Latency vs Bandwidth: The Real Performance Story

Here’s a critical insight that many people misunderstand: latency, not bandwidth, is the primary bottleneck for most website loading.

Bandwidth: The Pipe’s Width

Bandwidth measures how much data can flow through your connection per second, typically measured in Mbps or Gbps. Your router’s specifications might advertise WiFi 6 with “up to 1200 Mbps,” but this theoretical maximum is rarely achieved in practice due to:

- Distance from the router – WiFi signal degrades with distance

- Interference – Other WiFi networks, microwaves, cordless phones

- Overhead – Protocol overhead, retransmissions for corrupted packets

- Device limitations – Your device might only support WiFi 5, not WiFi 6

Latency: The Delay Factor

Latency (measured in milliseconds) is the time it takes for a packet to travel from your device to a server and back. This is influenced by:

- Physical distance – Speed of light in fiber/copper limits propagation

- Number of hops – More routers = more delays

- Router processing time – Each router adds microseconds to milliseconds

- Congestion – Queuing delays when routers are busy

- Connection type – Fiber is faster (lower latency) than DSL or satellite

Why Latency Matters More for Web Browsing

Consider loading a typical website. Your browser might make 50+ separate HTTP requests for HTML, CSS, JavaScript, images, and APIs. Each request-response cycle requires:

- Time to send the request (proportional to size/bandwidth)

- Time for request to reach server (latency)

- Time for server to process (server-side latency)

- Time for response to reach you (latency)

- Time to download the response (proportional to size/bandwidth)

Steps 2 and 4 are pure latency—they happen regardless of bandwidth. If latency is 100ms, then each of those 50 requests will experience at least 100ms delay just in network travel.

Increasing bandwidth from 100 Mbps to 1000 Mbps only affects step 5. It doesn’t help with steps 2 and 4.

The 14KB Rule

Here’s a practical example of how TCP and your router interact. When a server first sends data to you, it uses a mechanism called slow start. TCP initially sends just 14KB (about 1,000 words of text) in the first round trip. The router forwards this, it reaches you, your device acknowledges it, and the acknowledgment travels back.

If that 14KB packet successfully reached you and was acknowledged, the server doubles the transmission rate to 28KB. This continues, exponentially increasing the data rate, until packets start getting dropped (indicating network congestion) or the maximum rate is reached.

This is why latency is critical in the first moments of loading a page. Your browser can’t even start downloading images until:

- The HTML document arrives (latency)

- The browser parses it (local processing)

- It determines which images to download (processing)

- It sends those requests (latency again)

If latency is high, even with massive bandwidth available, the page feels slow because you’re waiting for each step to complete.

Common Router Bottlenecks

Understanding what happens in your router helps identify and fix performance issues.

Wireless Congestion

If you’re using WiFi, your router is handling much more complexity than if you were wired. Your router must:

- Manage channel selection (2.4GHz vs 5GHz bands)

- Handle interference from neighboring networks

- Re-transmit packets when corruption occurs due to weak signal

- Manage power-saving features on connected devices

WiFi latency is typically higher than wired connections due to these factors. If you’re experiencing slow website loading over WiFi, try connecting via Ethernet to see if it’s a WiFi issue.

Connection Table Exhaustion

Your router maintains a NAT connection table with limited entries. Under heavy usage (especially if you’re running P2P applications, downloads, or have many devices), this table can fill up. When full, the router may:

- Drop new connections

- Refuse to accept new requests

- Become unresponsive

Older or budget routers might support only 8,000-16,000 concurrent connections. High-end routers support 500,000+.

QoS Misconfiguration

Quality of Service settings allow you to prioritize traffic. A misconfigured QoS policy might:

- Throttle web traffic to prioritize a gaming console

- Limit bandwidth per device

- Create artificial bottlenecks

DNS Server Issues

If your router is configured with a slow or overloaded DNS server, every website visit begins with a delay. Your ISP’s DNS server might be:

- Geographically distant

- Overloaded

- Misconfigured with poor caching policies

Thermal Throttling

Routers generate heat, especially under sustained load. Some routers throttle performance when they overheat to protect components. This is why:

- Routers benefit from ventilation

- Placement in enclosed spaces (inside a cabinet) reduces airflow

- Continuous high traffic can cause throttling

How to Optimize Your Router Performance

Armed with understanding of what happens inside your router, here are practical optimizations.

1. Update Your Router’s Firmware

Firmware updates often include:

- Security patches (critical for routers)

- Bug fixes

- Performance improvements

- Updated routing tables (BGP data)

Check your router’s admin interface or manufacturer’s website monthly for updates.

2. Optimize DNS Settings

Replace your ISP’s DNS with a faster alternative:

- Cloudflare: 1.1.1.1 (widely regarded as fast and privacy-focused)

- Google: 8.8.8.8 (reliable, though less privacy-focused)

- Quad9: 9.9.9.9 (focuses on security/malware blocking)

Configure this in your router’s WAN settings. All devices on your network will immediately benefit.

3. Reduce Wireless Interference

If you’re on WiFi:

- Move the router to a central, elevated location

- Switch to the 5GHz band (less congestion than 2.4GHz, though shorter range)

- Use WiFi analyzer tools to find the least congested channel

- Keep the router away from microwaves, cordless phones, and metal objects

4. Wired Connections for Bandwidth-Heavy Devices

For devices that need low latency or high bandwidth (gaming consoles, streaming services, servers):

- Connect via Ethernet if possible

- Use PoE (Power over Ethernet) for devices like security cameras or APs

5. Implement Intelligent QoS

Configure QoS to:

- Prioritize real-time traffic (VoIP, video calls)

- De-prioritize P2P and torrent traffic

- Allocate bandwidth fairly among devices

6. Monitor Router Temperature

Ensure your router has adequate ventilation:

- Don’t stack devices on top of it

- Keep it away from heat sources

- Consider adding a small cooling fan for high-traffic routers

7. Reduce Connected Device Count

Each connected device adds to the router’s processing load. Regularly:

- Identify connected devices (most routers show this)

- Remove forgotten or dormant devices

- Use “forget network” on devices you’re not regularly using

8. Test Your Current Performance

Use these tools to establish a baseline and monitor improvements:

- ping command – Measures latency to a serverbash

ping -c 4 example.com - traceroute – Shows the path and latency to each hopbash

traceroute example.com - speedtest.net – Measures bandwidth and latency

- Cloudflare Speed Test (speed.cloudflare.com) – Similar to speedtest but faster

9. Consider a Router Upgrade

If your router is:

- Over 5 years old

- Struggling with 20+ connected devices

- Not supporting WiFi 6 (802.11ax)

- Experiencing frequent disconnections

An upgrade can provide significant improvements. Modern routers have:

- Faster processors (handling packets quicker)

- Larger connection tables

- Better cooling

- Improved routing algorithms

- WiFi 6 or WiFi 6E support

10. Alternative: Advanced Router Options

For business use or high-traffic environments, consider:

- OpenWrt Custom Firmware – Gives granular control over routing and QoS

- pfSense/OPNsense – Professional-grade firewalls with advanced routing

- Raspberry Pi + OpenWrt – Low-power alternative for small networks

- Managed Switches + Separate Routers – Separates routing from switching for better performance

Conclusion: Your Router Is More Than a Magic Box

What happens inside your router when you open a website is a orchestrated dance of protocols, hardware processing, and network decisions.

From the moment you hit Enter, your router:

- Forwards your DNS query to find the website’s IP address

- Facilitates the TCP handshake to establish a connection

- Translates network addresses (NAT) to protect your private network

- Processes each packet with firewall rules and QoS policies

- Forwards your data across the internet through multiple intermediate routers

- Receives responses and routes them back to your device

Understanding this process demystifies network performance issues and reveals where to optimize. Most website loading slowness comes from latency (network delays), not bandwidth. A slow DNS server, distant routing, or router congestion will impact every webpage you visit more than a slow internet connection ever will.

Whether you’re running a personal blog, managing a small business network, or troubleshooting why your streaming keeps buffering, these fundamental concepts of how routers work apply universally. Invest in understanding and optimizing your network layer, and you’ll see measurable improvements in user experience—something that directly impacts everything from SEO rankings to customer satisfaction.

The next time you open a website, remember: your humble router is doing far more than you probably realized.